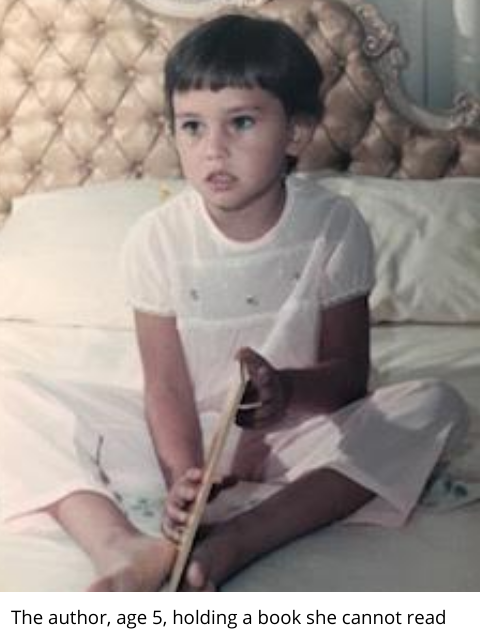

Notes from a bookseller’s daughter

Books were an integral part of my childhood. Not just because my family valued reading, but also because my dad managed bookstores. Some of my earliest memories are of my little brother and me running up and down the stacks after closing hours giggling and screaming. Of course, not everyone giggled at the sight of books, my mom often grumbled about his penchant for filling the house with them, but the book tsunami was unstoppable! To sum it up, I never wanted for books and could easily challenge you to find another person who had more of a print-rich environment than the bookseller’s daughter.

Eventually, I ventured out of my book-filled home to attend school. In first grade I was sent to an ultra-progressive school that was militantly whole language. Although we had Reading Time daily, nobody gave me direct instruction on how to decode. Thus, Reading Time consisted of me dutifully looking at pictures in children’s books, and wondering why nobody wanted to teach me what to do with them. I was a shy little girl who did not frustrate easily, and certainly did not want to upset the nice hippie teachers at the school, so I never made a fuss. Why would I? Soon Reading Time would end, and I could return to more exciting activities like feeding the school’s goats. Unfortunately, this idyllic 1970s hippie chapter of my life came to an end. We moved to Miami where I entered a 2nd grade public school; there a teacher informed my mortified bookseller dad that I was illiterate. Being a take-charge, problem-solving type of guy, he immediately found a literacy specialist to remedy the situation, and I subsequently became the quintessential nerdy girl. What else would you expect from the bookseller’s daughter?

Does a print-rich environment lead to literacy?

As the chapters of my life passed, I found myself in teacher’s ed school preparing to teach high school French. And if there is one thing those Ed schools like to harp on is the importance of the print-rich environment for our students. But where does this assumption come from? Has the theory been tested? From my own experience, being surrounded by books did nothing to hone my decoding skills, and conversely one could also assume that there are excellent decoders who come from homes with empty bookshelves. Why is this theory taken as gospel? What would happen if I were to distribute violins to every child in my city with minimal music instruction, would you expect to create one Itzhak Perlman or an entire city of them? And yet, the theory that book exposure in and of itself creates a literate individual is highly regarded, not only in education, but in the greater culture at large. And like any idea that captures the imagination there is some truth to it. We have all heard of that child – the one with sophisticated literary parents who effortlessly learns to read before entering school like the proverbial fish to water. They do exist. However, any cognitive scientist will tell you that these children tend to be outliers – precocious outliers, who are not necessarily more intelligent than any other child.

Do we place undue pressure on parents to create a print-rich environment?

We can always count on American culture to entertain two completely opposing strains of thought. While learning to read is presented as something natural (just sit them in front of a print rich environment), there is also the idea that a herculean effort is required from parents (get that infant on a Mommy & Me reading schedule). In fact, this parental pressure often begins during periodic well baby visits. In the popular Reach Out and Read Program pediatricians promote literacy to parents – especially low-income parents. In these visits they encourage parents to incorporate pre-literacy activities with their child such as regular read-alouds, story-telling, library visits etc., thus creating positive associations with literacy. As this is a program created by pediatricians, you can bet your diapered bottom that science informs their initiative. In fact, if you visit their website, you will see a great deal of research emphasizing that crucial window (up until 3 years old) when the brain has greater plasticity. Here is an example:

Such early literacy experiences in the home are particularly important during infancy and early toddlerhood because they take advantage of early brain plasticity, building neuronal connections that enable later reading and academic success (Shore,1997;Snow&Tabors,1996)

However, when pediatrician, author and Reach Out to Read activist Perri Klass MD says: …literacy is so much more than decoding print I feel the good doctor is getting in over her head. For the pre-K set, it is absolutely true. Encouraging parents to tell stories, look at picture books, and read-aloud to very young children definitely set the stage for later literacy. However, getting a child to memorize words in a picture book and decoding are two separate activities. Decoding is the ability to make sound to letter correspondences which is real reading – something that is inadequately taught in U.S. school systems.

How do schools reinforce this misconception?

They say the road to hell is paved with good intentions. So, when Ed Schools get a hold of the kind of research promoted by Reach Out to Read, it takes on a fun house mirror effect – distorting it beyond recognition. If you want proof of this distortion, walk into any K-8 classroom and you will encounter an overwhelming sensory overload. Erika Christakis expresses this obsession in her book The Importance of Being Little: What Preschoolers Really Need from Grownups (2016)

First we’ll bombard you with what educators call a print-rich environment, every wall and surface festooned with a vertiginous array of labels, vocabulary list, calendars, graphs, classroom rules, alphabet lists, number charts, and inspirational platitudes – few of those symbols you will be able to decode, a favorite buzzword for what used to be known as reading(33).

All through elementary, middle and high school, the idea of the print rich environment continues to hold sway; cluttering classroom walls as though the bombardment of text will, by sheer force of will, create a literate cohort.

Are we parent-shaming struggling readers?

Start with parental pressure to read to children from birth and combine it with school systems that are strong on print rich environments and weak on systematic phonics training, and it is inevitable that families of struggling readers are to some degree scapegoated when the real work of decoding begins. In the article It’s Not Enough to Mean Well Margaret Goldberg from the Right to Read Project reflects on this:

I didn’t understand that my students were struggling not because of problems within themselves, but because of the instruction they had (or hadn’t) received… I was not consciously aware of how classist and racist ideas permeated conversations with my colleagues. Classism was cloaked in seemingly harmless phrases like, “His parents don’t read to him,” “Education is just not that family’s priority,” and “They are from out of the [school] district.”

Not only do teachers and administrators fall prey to the fallacy that children who are consistently read to will become accomplished readers, but apparently there are children’s book authors who join in as well. Recently a controversy erupted when Mem Fox, a children’s book author, appeared on an Australian tv program and said:

If every parent, or caregiver… read aloud a minimum of three stories a day to children in their care, we could eliminate illiteracy within one generation.

Aghast by this statement, Ann Castles a cognitive scientist in the field of reading disorders and dyslexia, put out a call on Twitter to the parents of struggling readers to share their frustration and heartache. She then collated these narratives in a letter to Fox explaining why these attitudes towards literacy are hurtful to so many people. Soon after The Sydney Morning Herald printed many of these gut-wrenching accounts from highly educated parents who dutifully read to their children, yet spent years desperately trying to get their struggling readers the help they needed. Feeling shamed and alone, many of these parents are unaware of their numbers. Castles estimates that 1 in 10 children will struggle to read (even with good teaching) and these children will continue to struggle well into primary school years and even high school without intensive intervention and support.

As for me, the bookseller’s daughter, I was lucky enough to have had a teacher who identified my reading deficiencies, and a family with the means for private tutoring; but I am haunted by thoughts of how my life would have changed had that not been the case. Would my parents have been viewed as deficient? Would they have been under suspicion for not having read to me enough as a child? In fact, thirty years later, at the exact time I was finishing my Masters in Education, my own son was identified as a struggling reader. Having completely digested the fallacy from Ed School that children who are read to on a regular basis magically become strong readers themselves, I vividly remember being racked with unnecessary guilt. Where did I go wrong? I read to him every day since he was a toddler, I brought him to bookstores to choose books that interested him, and of course I got him tutoring to remediate the situation. Yet, nothing helped until he received systematic phonics instruction.

How can we help the 60%?

Like many of the parents in the article from the Sydney Morning Herald, it took years before my son got the help he needed. According to a popular infographic known as The Ladder of Reading by the Canadian reading specialist Nancy Young 40-50% of children need a moderate amount of explicit, systematic instruction in phonics and 10-15% need prolonged instruction, with extensive repetition (dyslexia). Seeing these statistics, not only made me realize that my experience was not unique, but also spurred me on to try my hand at Precision Teaching. Perhaps I could remediate one of the 60% during this very strange summer – a summer where everyone is home-bound from the pandemic.

As the days passed with my struggling reader, she began to pour her heart out to me: I can’t keep up when we read chapter books in school, I can’t do it, I watch the other kids fill out comprehension questions and I have to make up answers because the teacher doesn’t like it when I leave them blank, I don’t like reading – it’s boring and hard. Here is a bright, clever, funny girl making extraordinary progress, yet it is hard to stop her from self-identifying as the dumb kid who cannot keep up in class. Think about it honestly, if you found the act of reading difficult and frustrating, do you think receiving a bunch of books would somehow make things better?

Dork Diaries

As I worked with this student using a curriculum of systematic phonics with fluency goals, I vowed that once I got her to read at 175 words per minute I would go all B.F. Skinner and give her a reward. Her mother had been trying for years to get her interested in books to no avail. When I questioned my student one on one, there was only one book that had any pleasant associations for her — Dork Diaries, but ONLY because she liked coloring the drawings.

The afternoon before my tutoring session, I spent some time in a familiar childhood space – the local bookstore where I purchased Dork Diaries. Later, that day she reached my fluency goal, and I joyfully presented her with the book. We read the first diary entry together, and I laughed at how much she picked up on the tone with her ultra-expressive read aloud. She really enjoyed seeing me respond to her performance; a good sign that the negative associations with reading were starting to wither. However, I gave it a 50/50 chance that she would read the book on her own for pleasure, as avoidance is a difficult behavior to overcome. But later that evening while cooking dinner I received a text from her mom: She is reading on her own. This is the first time I have ever seen her read for pleasure. Thank you. So, take a cue from the bookseller’s daughter. A print-rich environment will never in and of itself create enthusiastic readers, but if you do care about literacy — give children reading programs that offer systematic phonics, as it will pave the way for effortless and dare I say joyful reading.