The Science of Reading has been in the news a lot recently, and not surprisingly, many people (including a lot of teachers) find the sheer amount of information it involves overwhelming.

So, the basics: the Science of Reading is not a movement or a belief system. It is a vast body of research based on hundreds of studies conducted by dozens of researchers over many decades, and involving fields in the social and hard sciences such as psychology, linguistics, and neuroscience. While researchers still have questions about the exact processes by which skilled reading develops, a sufficient number of studies have produced similar results to allow them to conclude that certain things are true and others are not.

The goal of this post is to cover five of researchers’ most important findings, ones that are most directly connected to whether a reading program has the potential to be effective.

Note the word “potential”: children arrive in school with different backgrounds and have different sets of needs, and there is no single program guaranteed to be work for all students. That said, if you’re not sure whether a given program supports “the science of reading,” consider whether it is consistent with the following points.

1) Reading Is Not a Natural Process

Unlike human speech, which evolved naturally over hundreds of thousands of years, written language was only invented between 5,000 and 6,000 years ago; there is no natural developmental window during which young children automatically become able to match words to print. This is an acquired skill that most children require some degree of direct instruction to master, with certain students requiring much more extensive teaching than others.

In order for children to be ready to read, the relevant parts of their brains (visual- and speech-processing centers) must be sufficiently developed; they must also have a high enough level of phonological (sound) awareness to understand relationships between sounds and letters/groups of letters. If the second condition is not met, children will struggle to read, regardless of their age.

Furthermore, any program based on the assumption that children will naturally figure out how to read, in the absence of explicit instruction in how letters correspond to sounds and words, is virtually guaranteed to prevent many students from reaching their potential as readers.

2) Instruction Must Be Systematic

While the jury is still out on which type of phonics program is best, it is clear that to be effective, a program must teach letter-sound relationships in a clearly defined sequence, with simpler, more straightforward skills being introduced before more complex ones, and concepts gradually building upon one another.

This is particularly important because English has so many exceptions; if standard patterns, alternate patterns, and exceptions are not taught in a clearly defined way, then there is significant potential for confusion.

This stands in contrast to embedded phonics instruction, in which letter-sound relationships are discussed inconsistently and only in the context of specific words. When phonics is taught haphazardly, important letter-sound correspondences (particularly ones involving vowels) will almost certainly be overlooked, leading to gaps in children’s knowledge.

In addition, beginning readers have limited working memory: systematic phonics relieves children of having to juggle more concepts than they can manage by providing a logical sequence in which concepts are continually reiterated, applied, and built on.

That said, phonics should not be taught in isolation; to be fully effective, it must also be integrated with other subjects (e.g., writing), and children must be given ample opportunity to practice applying their skills.

3) The Simple View

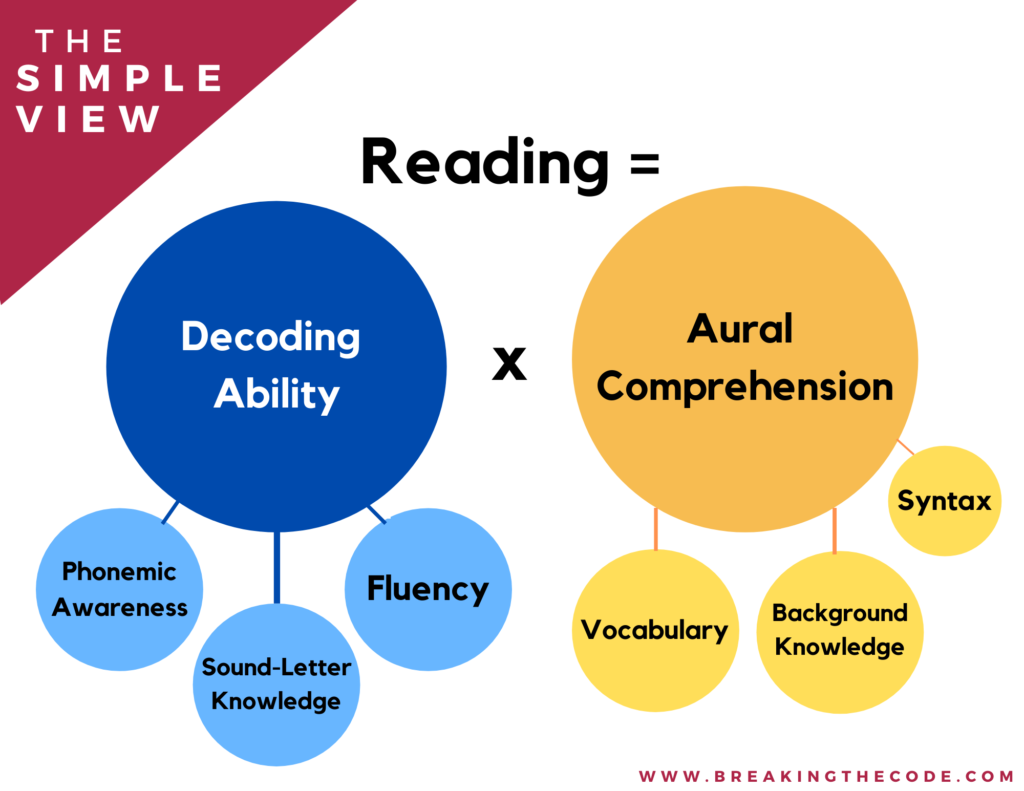

First laid out in a 1986 paper by Gough and Tunmer, the Simple View has become the accepted model of reading within the mainstream scientific community. It states that:

Reading = Decoding Ability (connecting strings of letters to words) x Aural Comprehension (including vocabulary, syntax, and background knowledge).

Note that reading the product rather than the sum of the two parts: if either is missing, a child cannot read.

By definition, reading includes a visual component: a (non-visually impaired) child who cannot decode, cannot read—no matter how well they understand spoken language. Likewise, it does not matter how well a child can literally decipher words if they cannot understand the meaning. Both parts must be present.

An understanding of the simple view is crucial to diagnosing reading difficulties, which can come from either the decoding or the comprehension side, or both.

For example, it makes no sense to focus on comprehension if a student can understand age-appropriate texts read aloud but has difficulty blending letters together to form words, or cannot distinguish between sounds well enough to consistently match them to the right letters.

On the other hand, if a child can decode a text quickly and accurately but is unable to answer basic questions about it, then only comprehension work is needed.

Note that in many cases (“garden variety reading” problem), difficulties on both sides are common. To pinpoint where the problem areas lie, however, it is necessary to consider the two sides separately.

The simple view is also crucial because it indicates that an effective reading program must explicitly develop both decoding ability and broad comprehension skills (including vocabulary and general knowledge) simultaneously.

4) Phonemic Awareness

Phonemic awareness is the ability to identify the individual sounds that make up words.

For example, the word dog has three phonemes: d, aw, and g.

The word shape also has three phonemes: sh, ay, and p.

This is an aural skill only—it does not involve letters or words.

Phonemic awareness is perhaps the most crucial pre-reading skill: if children cannot consistently identify, distinguish between, and/or manipulate sounds, they will struggle to connect them to letters and groups of letters, making phonics ineffective.

Recognizing vowel sounds—particularly short vowels—is especially challenging for many children.

In such cases, the underlying aural issue must be addressed in order for progress to be made with written language. Children will need to practice blending (putting together), segmenting (taking apart) and manipulating (changing and substituting) sounds.

Note that breaking words down into phonemes is not a natural skill—in everyday speech, sounds are frequently elided, dropped, or pronounced unclearly—and that some children may need considerable explicit instruction and practice to master it, particularly if English is not their/ their family’s first language.

5) Orthographic Mapping

Orthographic (or-tho-GRAPH-ic) mapping involves the formation of letter-sound connections to bond the spellings and pronunciations of specific words in memory. Or, put more simply, it is the process by which the brain memorizes how words look-sound.

This process, which involves both visual and auditory regions of the brain, makes words available for automatic retrieval, allowing skilled readers to process text at the speed of sight (approximately 200-300 words per minute).

Phonics directly supports orthographic mapping because it is designed to build and solidify relationships between sounds and letters/sequences of letters. Children with solid decoding skills can learn a word to the point of automatic recognition after only a few exposures.

In addition, studies on the eye-movements of readers have revealed that skilled readers attend to almost every word in a sentence and process the individual letters that compose each word, looking at each one for a fraction of a second (McConkie and Zola, 1987; Adams, Beginning to Read: Thinking and Learning about Print, 101).

Combined with orthographic mapping, this finding provides a powerful explanation for why three-cueing/MSV methods are ineffective. To reach the point of being able to process text instantaneously, children must attend carefully to the specific sequences of letters on the page and match them to sounds; over time, these correspondences are recognized more and more quickly, until they become automatic. Any method that involves children repeatedly moving their eyes away from the text (e.g., to look for context clues) disrupts the development of this process.

Research by Stanovich (1984) and Nicholson (1991) indicates that struggling readers focus on context clues far more than strong ones, and that as children become more proficient readers, they depend less on context to identify words.