In 2000 the National Reading Panel (NRP) published their findings—a thorough piece of research on the issues of reading instruction in the USA. The findings are interesting reading, and of course, twenty years later, the changes that the panel recommended have been never been fully implemented. The Panel recommended Phonics, Fluency, Phonemic Awareness, and Comprehension as essential elements. Most reading programs now say they offer fluency in their systems and that they offer all of the critical elements. Now, as the reading wars heat up again, whole language systems are making the dubious claim that they offer everything that the NRP recommended.

Of course, long before the NRP recommended fluency, a small number of very intense professionals were already using it as a tool for instruction of almost every kind of learning, not only reading. A separate form of instruction and measurement had begun in the 1990’s called Fluency Based Instruction (FBI). In fact, I had already reserved the site named FluencyFactory.com. There were fully developed, wide-ranging curricula in every academic area—all the way to college courses on mechanical engineering—that were built around the idea that mastering the basic elements of a skill is measurable and critical to mastering the complete skill.

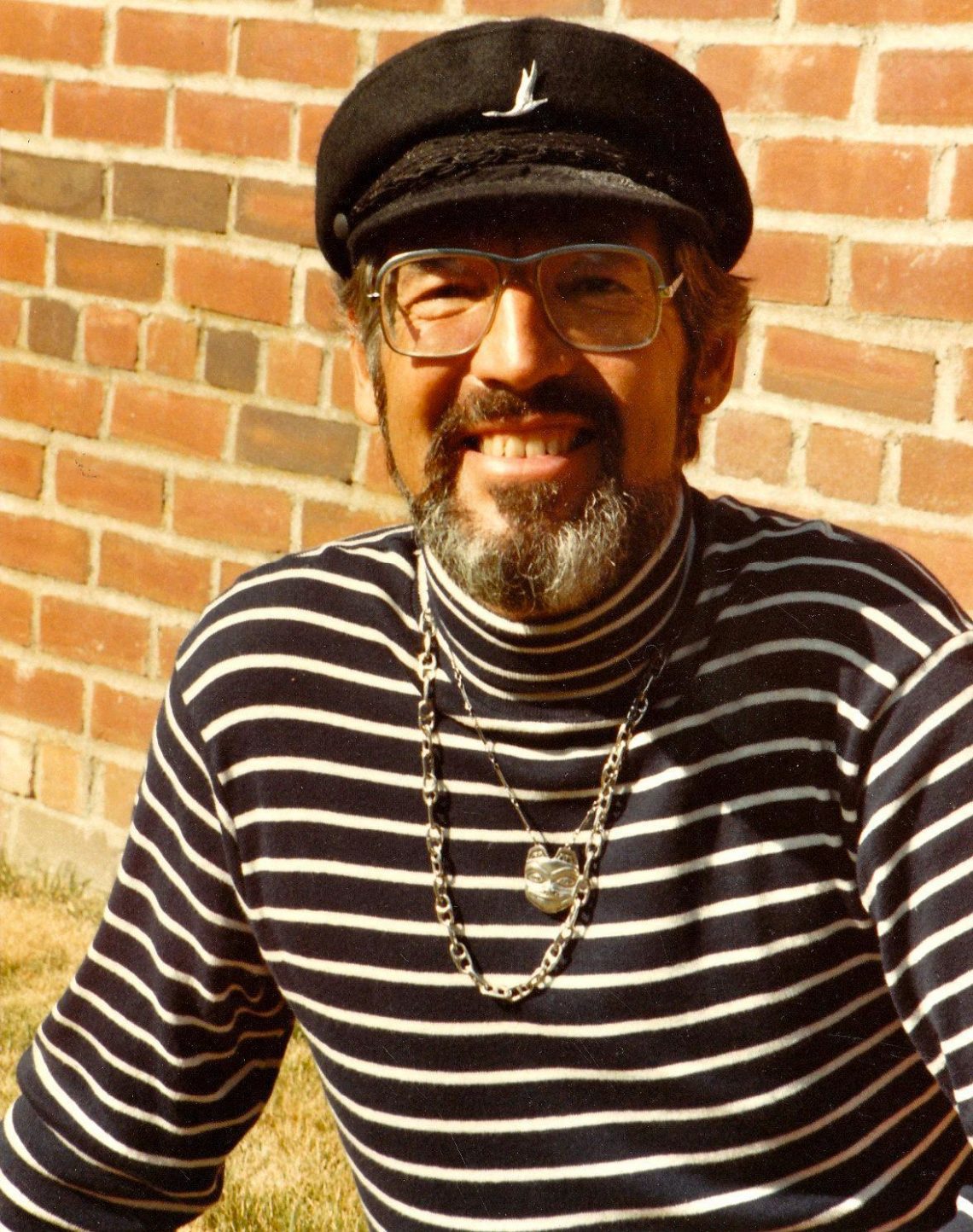

We weren’t psychic, we were followers of a truly remarkable man, Dr. Eric C. Haughton, who had ideas that transformed our way of thinking about how best to teach and what to expect as we taught. To best understand Eric’s profound impact on so many learning centers, it is important to get an idea of what he taught us about fluency and its primacy for instruction.

Reading is perhaps the easiest domain to examine. Eric was appalled when I showed a chart that charted instruction of an autistic student who was reading at about 20 words per minute. “That’s not reading, READING is 200 words per minute aloud. You need to assure that students are reading that fluently before you add more words to their reading vocabulary.” Eric also urged us to look at the simple behavioral formula behind reading.

It is this basic.

We took that challenge and began finding materials that supported our learners in becoming fluent. For example, a young autistic student named Frank would name every little scrap of paper on walks, recognizing the fast food maker by the color. Frank would immediately name each scrap, so a walk would include recitation of “Burger King, McDonalds, Dunkin Donuts.” We were using a reading instruction program with Frank and he was struggling with that. We grabbed the wrappers that he knew so well and cut them into small squares, then glued them onto a page. Almost immediately he could read those colors as words at 200 wpm. We mixed in the reading vocabulary and he was able to master those as well. We tried it and were amazed to find that we could quickly teach our students to read fluently—even at 200 words per minute! The reading programs we were using were NOT very good, but were a place to start. As we used them, we learned about other, better programs and switched to those.

Looking at reading using this simple formula made it possible to plan instruction in which students graduated from naming pictures, objects, people to letters, numbers, symbols—and then to build fluency at each step along the way so that students have a durable skill. We have learned that students must master phonemic awareness, a full set of phonics, and practice reading everything from lists to complex literature. The approach that works amazingly well is one in which the simplest elements of a Learning Channel set are built to a high level of skill, then the materials are changed to increasingly more complex levels. Learning Channels are a way of looking at how we get information and how we process it. In the Precision Teaching Community, we frame the instruction that we are doing with this framework. Eric and Elizabeth talked about the way that they helped one little boy, a quadriplegic kindergartener who was at one point diagnosed as severely retarded.

Eric helped his wife Elizabeth plan for this student, Terry Harris. Terry had cerebral palsy and walked with crutches, as previously mentioned he was not regarded as capable by many professionals. Elizabeth was teaching him to write his name, but it had taken her from September to Christmas vacation to teach him how to write his first name. Fourteen weeks to learn to write T-E-R-R-Y.

Elizabeth wondered if there wasn’t a better way to teach him to write his last name. There were two R’s in it, so that would help, but it still seemed as though there must be a better way.

Eric asked her if Terry could write 250 to 200 stokes (|||||) in a minute. Elizabeth replied that Terry was quadriplegic—Eric replied, “I didn’t ask what he looks like Elizabeth—can he do 250 to 200 strokes per minute or not?” Elizabeth admitted she didn’t think so. “Can he do 140 to 120 0’s in a minute?” Once again Elizabeth said he probably could not. “Those are the elements that make up the compounds for every letter or number we write. If those elements are not fluent, then learning to write numbers and letters will be very slow and labored.”

Returning to school Elizabeth and Terry spent the next three weeks working on |||| and 00’s. Terry went from about 50 ||||’s to over 175, and from 25 0’s to over 90. “But Terry and I were getting tired of this drill, and we were ready to try going back to writing his name.” They were both ready to try something different.

It took five minutes for Terry to learn to write “Harris.”

Eric urged us to help our students find ways to use Learning Channels to think about everything we were teaching..

Outputs –> Say Mark Write Think Do Feel (emotion)

Inputs

See

Hear

Touch

Sniff

Taste

Think

Feel (emote)

This simple matrix helps us to understand what channels will be needed for a student to perform a complex skill. Some performances are yoked—taking an SAT involves seeing + thinking/marking; reading a word list might be just seeing/saying. Our job is to develop our children as widely as we can, with thinking and feeling skills as well as with easily measurable skills. Please also note the Precision Teaching community, while a behavioral community, allows us all to measure our inner behaviors. Silent reading? Please time and count. Emotion about a loss? Please count the daily occurrences. We are complex creatures with many abilities, and as we become more competent teachers we can measure more diverse performances, create more skills and more confidence.

It was wonderful to see how quickly our severely disabled students could reach high levels of performance, but that was not the magical part. What was totally amazing was how quickly these performances transformed worried, uncertain, sometimes violent students into happy and confident learners. Now, years later, I still assure that the beginning student performances are accurate and fluent before adding more vocabulary. It’s the “wax on, wax off,” approach to instruction. Now, thanks to Eric’s instructions, when we teach new materials to our students we assure that they are fluent readers at every step—long before they can read a wide variety of materials. This elemental mastery permits rapid, enjoyable learning, with so much less struggling.

Eric Haughton provided insights that transformed so much of what many of us now do daily, releasing many students to enjoy learning and develop broad, deep skills in every dimension.

That’s why we do so much carefully planned work on elements of handwriting, reading and math. Eric led us to a method that has been powerful for assisting students at every level.